- 'tis the season

- 3rd Ward

- 8 x 10

- 8 x 10 mag

- 31 Women in Art Photography

- 2009 Project Grant Recipients

- 2010 Project Grant Recipients

- 2011 Project Grant Recipients

- 2012 Project Grant Recipients

- Advertising

- After Color

- Amani Olu

- Amy Arbus

- An-My Le

- Andreas Laszlo Konrath

- Andres Serrano

- Andrew Lichtenstein

- Angela Strassheim

- Anna-Sophie Berger

- Anna Bauer

- Anna Beeke

- Annabel Mehran

- Anne Menke

- Aperture Foundation

- Archival Pigment Printing (Inkjet)

- B+W Silver Gelatin Printing

- Barbara Crane

- Ben Fink Shapiro

- Ben Grieme

- Bill Armstrong

- Bill Jacobson

- Blair Getz Mezibov

- Bonni Benrubi Gallery

- Boogie

- Bravin Lee Programs

- Brea Souders

- Brian Nice

- Bruce Silverstein

- C-41 Film

- Canteen Magazine

- Cao Fei

- Cati Borruso

- Charmichael Gallery

- Chris Rhodes

- CLAMPART

- Colnaghi

- Compsiting

- Conde Nast Gallery

- Conde Nast Traveller

- Conventional C-Printing

- conventional c-prints

- Cosmopolitan Magazine

- Cristina De Middel

- Daniel Reich Gallery

- Danny Clinch

- Dave Krugman

- David Battel

- David Benjamin Sherry

- David Gahr

- David leventi

- David Sherry

- David Uzochukwu

- Debby Hymowitz

- Denny Renshaw

- Diana Zeyneb Alhindawi

- Digital-C Printing

- digital imaging

- Dominique Nabokov

- Editorial

- Edwynn Houk Gallery

- Elad Lassery

- Elinor Carucci

- Emiliano Granado

- Emmanuel Fremin Gallery

- Envoy Gallery

- Erica Allen

- Erika Larsen

- Eva O'Leary

- exhib

- Exhibition Mounting

- Exhibitions

- Fabiola Menchelli

- Fader Magazine

- Film Processing

- Fotografiska New York

- Framing

- Frederic Lagrange

- Frédéric Brenner

- Galerie Karsten Greve

- Galerie Number 8

- Gavin Brown's Enterprise

- Griffin Museum of Photography

- Heather Darcy Bhandari

- Hello Mr.

- Hey Hot Shot

- Higher Pictures

- Humble Arts Foundation

- Imaging

- James Clar

- James Fuentes LLC

- James Mollison

- Janaina Tschape

- Jane Lombard Gallery

- Janet Borden Gallery

- Jan Staller

- Jason Kraus

- Jen Beckman Gallery

- Jennifer Karady

- Jennifer Livingston

- Jennifer Loeber

- jessica Eaton

- Jonathan Mannion

- Joni Sternbach

- Josh Olins

- Joss McKinley

- JTT Gallery

- Juergen Teller

- Julia Comita

- Julie Saul

- Justine Kurland

- Justin James King

- Karen Irvine

- Katherine Newbegin

- Kaufman Repetto

- Ken Regan

- Kodak

- Laura Levine

- Lawrence Beck

- Leica Gallery

- Leslie Fritz

- Liz Clayman

- Lombard-Freid Projects

- Look Book

- Louisa Marie Summer

- Magazine Covers

- Manjari Sharma

- Mark Leckey

- Martin Schoeller

- Max Farago

- Max Snow

- Meredith Danluck

- Michael Buhler-Rose

- Micheal McLaughlin

- Milagros de la Torre

- Mitchell Innes and Nash

- Mitch Epstein

- MIxed Greens

- Moab Paper

- Modern Weekly

- MoMA

- Morrison Hotel Gallery

- Mounir Fatmi

- Mounting

- Muse Magazine

- Museum Boxes

- Museu Oscar Niemeyer

- MZ Wallace

- Natasha Gornik

- New York Magazine

- Nicholas Vreeland

- Nike

- OH WOW Gallery

- Olivia Bee

- Paulette Tavormina

- Paul Kasmin Gallery

- Pedro Arieta

- Penelope Umbrico

- Peter Funch

- Philip Andelman

- Phillip Lim

- Picto

- PROXYCO Gallery

- Purple Magazine

- Ramis Barquet

- Raymond Depardon

- Reed Krakoff

- Renwick Gallery

- Rep.Limited

- Retouching

- Richard Finkelstein

- Richard Mosse

- Richard Renaldi

- Rick Wester Fine Art

- Rika Magazine

- Robb Hann

- Robert Klein Gallery

- Robert Levin

- Robert Mann Gallery

- Robert Polidori

- Robin Rice Gallery

- Rodney Smith

- Rolling Stone

- Ruth Orkin

- Scanning

- Sebastiaan Bremer

- SF Camerawork

- Sharif Hamza

- Sies + Höke Galerie

- Simon Colley

- slideluck

- Some Days ...

- Sonnabend Gallery

- Sony Square NYC

- Stefan Ruiz

- Steven Kasher Gallery

- Sunny Suits

- Susan May Tell

- Sze Tsung Leong

- Talia Chetrit

- Tarter Sauce

- Tema Stauffer

- the art street journal

- The L Magazine

- The Morrison Hotel Gallery

- The New Yorker

- The New York Times

- The New York Times Lens Blog

- The nicest things ...

- Theo Wenner

- The Propeller Group

- Thomas Dozol

- Tiana Markova-Gold

- Tim Barber

- Time Magazine

- Tina Barney

- T Magazine / The New York Times

- Trisha Donnelly

- Trunk Magazine

- Valario Spada

- Vogue Nederland

- WIP / Lightside Individual Project Grant

- Women in Photography

- Yossi Milo Gallery

- Zoe Crosher

- Zoe Ghertner

One night, three openings (all film processing customers!)

Frédéric Brenner

An Archaeology of Fear and Desire

Howard Greenberg Gallery

May 7 – July 3

David Leventi

Opera

Rick Wester Fine Art

May 7 – July 10

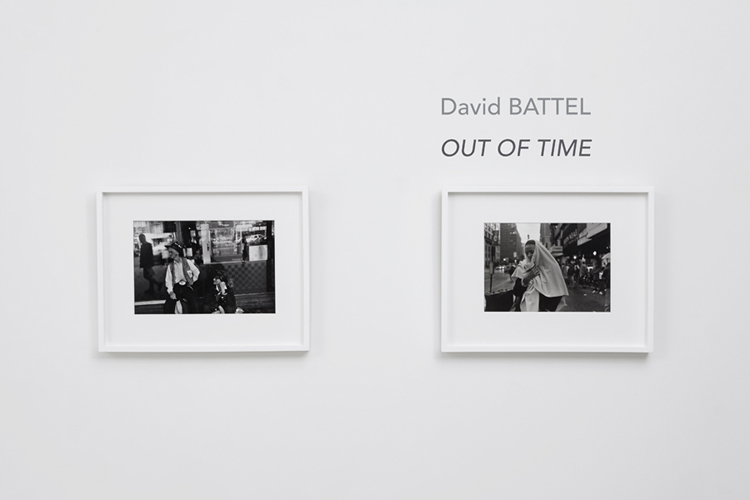

David Battel

Out of Time

Rick Wester Fine Art

May 7 – July 10

It’s not often that we see three of our wildly diverse customers having fancy openings in New York City on the same night. Yet on Thursday May 7th, David Leventi, David Battel and Frédéric Brenner all held court in various galleries showing off their work. And what’s even more oddly-coincidental is that these three guys are film shooters who process with us … we couldn’t have been more proud!

David Leventi: Proud papa in front of his Palais Garnier, Paris, France, 2009

For more on David Leventi’s Opera at Rick Wester Fine Art click here.

Read an additional post on David in our Project Archive here

See more of David’s work on his website here

David Battel at Rick Wester Fine Art

For more on David Battel at Rick Wester Fine Art click here

Frédéric Brenner: Sderot, 2011 from An Archaeology of Fear and Desire at Howard Greenberg Gallery

For more on Frédéric Brenner’s work at Howard Greenberg click here

Read an additional post on Frédéric in our Project Archive here

Explore Brenner’s project This Place here

Tags: David Battel, David leventi, Exhibitions, Film Processing, Frédéric Brenner, Rick Wester Fine Art

David Leventi’s Opera Houses (Something completely magical)

This post was stolen and modified from FT Magazine, an online publication of The Finacial Times, Ltd. By modified I mean that if you think this post is a tad wordy then you ought to check out the original here. Or put it this way, we’ll give a 15% discount on your next order to the first person who can answer this question:

Why did the famous Welsh bass-baritone Bryn Terfel break down in tears after his 2005 opening night performance as Wotan in Die Walküre at The Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London?

(Good luck)

October 21, 2011 10:08 pm

By Andrew Clark.

Opera tells us about what it is to be human. David Leventi photographs the view from the stage and Andrew Clark explores its architecture.

David Leventi: La Scala, Milan

It was a moment I will never forget. “This is the Callas spot,” said Riccardo Muti, at that time music director of La Scala, Milan’s opera house. He was indicating a precise point near the front of the stage, a few feet right of centre, where Maria Callas invariably took up position during performances there. The legendary diva reckoned it was the optimal place for projecting her voice during an aria. Woe betide anyone who got in the way.

Muti and I were on stage alone. La Scala’s U-shaped auditorium, with its rows of gilt-edged boxes and acres of red velvet, was lit up but empty. I was being given a private tour shortly after the theatre was renovated 10 years ago: the chance to stand on stage, surrounded by ghosts of the past, was the climax. The entire backstage area had been demolished. The old music director’s room, a heartbeat from the orchestra pit, had gone. The time-honoured water hydraulic system, which lifted the stage scenery into place, had been dumped. So, too, had the remaining stone columns of the medieval church of Santa Maria della Scala, on whose foundations the theatre was built in the late 18th century, and from which it took its name. Everything had been replaced by state-of-the-art facilities – everything, that is, beyond public view.

More

The only remnants of the old building were the auditorium, foyer and theatre frontage. Everything in these public spaces was the epitome of tradition – the giant chandelier above the stalls, the rows of identical boxes, the decorative 18th-century veneer. In the context of the cavernous new backstage area, with its concrete walls, computer-controlled lighting and sophisticated machinery, the view from the stage was undeniably beautiful – but also anachronistic.

Like most historic opera houses, La Scala resembles a violin or cello: it looks much the same as it did in the past and performs the same aesthetic function, but it has undergone all sorts of internal changes to make it conform to the technological advances and social conveniences of modern life.

“The interiors of old opera houses are a modern gloss on a traditional shape,” says Roger Parker, opera historian and professor of music at King’s College, London. “They are a bit like a fake antique – they’re meant to look old, but not in the way they would be if they had been left as originally built.”

Opera – the marriage of singing and theatre – began in early-17th-century Italy as a popular as well as courtly entertainment, but the theatres built to house it quickly evolved into upper-class meeting places, with an architecture embodying social hierarchy. The stalls and slips were for the lowest-ranking; the central boxes were for the highest. The important thing was not so much seeing what happened on stage as being seen. That explains the U-shaped auditoria of most surviving 18th-century theatres.

Boxes, paid for by their owners or by subscription, were positioned in a way that gave a better view of social peers than they did of the stage. There was no dimming of lights – the stage-event was just one part of a social occasion. People would receive visitors in their box, play cards and eat, or mingle in the corridors outside. Boxes had curtains: there was scope for all sorts of shenanigans while the performance was under way. Travellers to Italy in the 18th century invariably commented on what a noisy place the opera house was.

By that time the opera bug had spread north of the Alps. You can tell from the small court theatres in Bayreuth, Munich, Prague and Schwetzingen – all still worth a visit – that opera in the 18th century was very much an aristocratic preserve. Design and decoration were on a grand scale but capacity was often 500 or fewer.

In the 19th century, the rising urban bourgeoisie, educated and upwardly mobile, started footing the bill – a change reflected in the design and location of opera houses. They became a civic totem, occupying a central position in town planning – at the head of an avenue, as in Paris, or overlooking a prominent square, as in Geneva. Theatres had to be bigger, not just to satisfy increasing demand but to be financially viable. Space-taking boxes gave way to tiers of seats on open balconies. London’s Royal Opera House and Munich’s National Theater are good examples: the only boxes are at the side of the stage. The U-shape morphed into a wide horseshoe – a way of maximising capacity and improving sightlines – and the stalls became the most important place to sit.

David Leventi: Opéra de Monte-Carlo, Monaco

The pressure to provide more seats coincided with an increase in the size and sound of orchestras, leading to the creation of a pit in front of the stage. This signified a subtle change in the art form. Previously considered a theatrical event in which librettists and singers were the main focus, opera was now as much a musical event, with the composer (and later the conductor) rising in importance. Instead of addressing audiences from a thrust stage, singers were pushed behind the proscenium arch and forced to compete with more powerful 19th-century instruments. New vocal techniques were required to help them project over larger distances.

The only theatre architect to address this problem was Wagner. By placing the orchestra out of sight underneath the stage of his festival theatre at Bayreuth, completed in 1876, he enabled every word to be heard: the acoustic remains a wonder of the theatre world. But Wagner’s theatre creates a time-lag between the sound coming from the hidden pit and the sound created on stage, which conductors must learn to co-ordinate. It’s hardly surprising no one has replicated the design.

By the early 20th century, opera house architecture was undergoing another phase of development. In the US, where the arts have always been privately funded, high-capacity theatres became a necessity. Holding between 3,000 and 4,000 people, they make financial sense, but they also encourage over-singing and leave little room for the experimental. They lack intimacy.

David Leventi: San Francisco’s War Memorial Opera House

Some, such as San Francisco’s War Memorial Opera House, replicate the elegant facades and foyers that 19th-century architects employed to make a social statement. That statement is reinforced by the spectacle of the auditorium – grand not only in size but also in richness of decoration. The wealthy feel at home in this environment; the poor feel out of place.

This is not just an American phenomenon. Many European theatres oblige people in the cheap amphitheatre seats to enter and leave by a side door, a safe distance from those in expensive stalls and balcony seats, who come through the main entrance. When the Royal Opera House was renovated 11 years ago with a mission to be more socially inclusive, the internal layout was reconfigured: everyone now comes in by the same entrance. The Floral Hall, the theatre’s main socialising area, is connected to the upper circle by escalator. It is a visible tool of integration – and yet the overall style of the building remains the same. The main auditorium retains its grand 19th-century decoration. Behind it you may find nothing but old wood, but the veneer chimes with the fancy gowns, elaborate wigs and male make-up on stage.

Not all opera houses are fake antiques. In 1945 most German theatres lay in ruins, necessitating a rebuild. The new theatres were plainer than before, better equipped and more user-friendly: there are plenty of toilets, a convenience in painfully short supply in 18th- and 19th-century theatres. Berlin’s Deutsche Oper has no boxes, and all seats directly face the stage. The new buildings are relatively intimate spaces, with capacity well within the optimal 2,000 limit.

The problem on both sides of the Atlantic, as well as in Asia, where opera has proliferated over the past 20 years, is that opera house design remains glued to a 19th-century model. Look at the new theatres in Guangzhou, Oslo and Valencia. From the outside they are iconic buildings. Inside they are conventional, “and that must be one of the things dragging opera back to its past,” says Nicholas Payne, director of Opera Europa and a former head of the Royal Opera and English National Opera. “These theatres are great for La traviata and The Ring, but they don’t really work for Handel, and they’re increasingly inappropriate for the operas of today.”

The 19th-century theatre model arouses expectations of a certain type of spectacle and grandiosity, and this has limited opera’s development as an art form. Composers feel they have to respond by writing huge and expensive works. The most innovative operas of the past 50 years – such as Thomas Adès’s Powder Her Face, Britten’s chamber operas and Stockhausen’s Licht – were devised for alternative spaces, where the orchestra did not form a barrier between stage and audience.

Some companies have successfully explored ways of circumventing 19th-century theatre design. In its 2010 production of Henze’s Elegy for Young Lovers at the Young Vic, English National Opera demonstrated that opera can thrive “in the round”, given suitable resources and the right imagination.

Better-funded companies have gone for the “black box” solution – a chamber theatre, inside or adjacent to the main building, where stage machinery is minimal and the lighting rig flexible, encouraging the production team to reconfigure the way their audience views the performance. But at London’s Royal Opera House and the new Copenhagen opera house, the “black box” remains a sideshow, a sop to contemporary awareness. Both companies make their money by putting on Tosca and La traviata in the main theatre.

The most transformational events in recent years have taken place in converted factories or old exhibition halls – vast spaces that give the director and designer carte blanche to create a new production aesthetic. Many of these industrial-legacy buildings are situated in Germany’s Ruhr region, where local authorities have invested heavily to convert them into culture parks. At the Bochum Jahrhunderthalle in 2006, audiences viewed Bernd Alois Zimmermann’s Die Soldaten from movable seating blocks, running on rails above a performance space that extended like a catwalk from one end of the building to the other. Similar extravaganzas have been mounted in a former turbine hall at Gladbeck, an old exhibition hall in Cologne and a converted gas plant on the outskirts of Amsterdam.

“These relics of the industrial past are being appreciated more and more for their aesthetic value,” says Shirley Apthorp, who has reviewed these productions for the FT. “Drawing people out of the city centre [to see them] is part of preserving them.”

David Leventi: Teatro La Fenice, Venice

But, Apthorp points out, such performances depend on sophisticated acoustic trickery. They tend to be site-specific and cost a lot of money. Opera budgets are tight, and most productions are built to be shared: if sets for the Royal Opera’s latest Don Carlo had not been of a size to fit co-producing theatres in New York and Oslo, the show could not have been funded.

The only city to have entertained the idea of a completely flexible opera theatre is Lucerne in Switzerland, and its project remains unrealised, due to a legal battle over the estate of the late Christof Engelhorn, who donated $137m towards the cost. David Staples, of London-based Theatre Projects Consultants, says the plan involved a large room with multiple sinking/rising floor-panels for audience and orchestra, so that the performance could take place anywhere – in the middle, on either side or at the end.

“But you can’t achieve total flexibility,” says Staples. “As soon as you build one wall, you build a constraint. The alternative concept is to say: why not, in addition to having your creative team of composer, director, designer and videographer, why not have an architect who designs a specially commissioned environment for you every summer, like the Serpentine Pavilion in London? But that was too radical for the Swiss.”

Given that opera works well in traditional theatres, with natural acoustics and a shape evolved over a 400-year period, it’s hardly surprising most opera managements shy away from experiment. Many composers, too, believe the “archaic” configuration of the 19th-century opera house provides a useful discipline. “The opera world occasionally makes lurches into alternative spaces, but very rarely does one feel that space was needed for the opera concerned,” says British composer Julian Anderson, who is writing a new work for ENO. “I’d love my opera to be performed “in the round” – but the architectural space is a red herring as long as the composer can impose an imaginary world on the audience. It’s all about taking the spectator out of themselves.”

Anderson’s argument is borne out by the remarkable success of live relays from New York’s Metropolitan Opera to cinemas around the globe. A whole new public – the biggest that opera has ever had – is eagerly imbibing the imaginary world of opera not from a red-velvet box but, thanks to modern technology, from the comfort and convenience of a small movie theatre.

The Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London

About the photographs

The American photographer David Leventi has titled his series of opera house interiors “Björling’s Larynx”, after the great 20th-century Swedish operatic tenor Jussi Björling. As Leventi explains, these are the spaces in which his Romanian grandfather, Anton Gutman, never got the chance to perform. “He was a cantor who was interned in a Soviet prisoner-of-war camp from 1942-1948. The Danish operatic tenor Helge Rosvaenge, also a prisoner, heard my grandfather sing an aria from Tosca and gave him lessons. I grew up listening to him sing in our living room.” To date, Leventi has photographed 40 opera houses in Europe and the Americas, each from centre-stage and lit solely by the existing chandeliers and lamps. “I believe that the space itself can be the event,” he says.

Tags: David leventi, Film Processing